At Patrick Daniel Law, our Houston maritime injury lawyers are well-equipped to handle difficult maritime injury cases that other Houston maritime law firms find too complex. Houston maritime injury law, also known as admiralty law, has a lot of quirks and inconsistencies. It takes an experienced maritime injury attorney to be able to see these inconsistencies, and we find them every case that makes it to our Houston law office.

Houston maritime workers are at a disadvantage in some maritime cases. In other maritime injury cases, they have some advantages in their favor. But only a skilled Houston maritime attorney will be able to figure it all out. So, whether you’re in Houston, Harris County, Pasadena, Baytown or the outlying suburbs, if you’ve been injured at sea and are in need of a Houston maritime injury attorney, Patrick Daniel Law is here to help. Contact our Houston maritime lawyers for a FREE consultation.

Patrick Daniel is an icon among Houston maritime attorneys, gaining the distinction through 20 years of maritime law in Houston, Texas and around the Gulf Coast.

Patrick Daniel has argued maritime injury cases from both sides and has extensive experience, not only in the way Houston maritime law cases proceed, but also in the work that goes on at sea by employees of hundreds of Houston maritime companies.

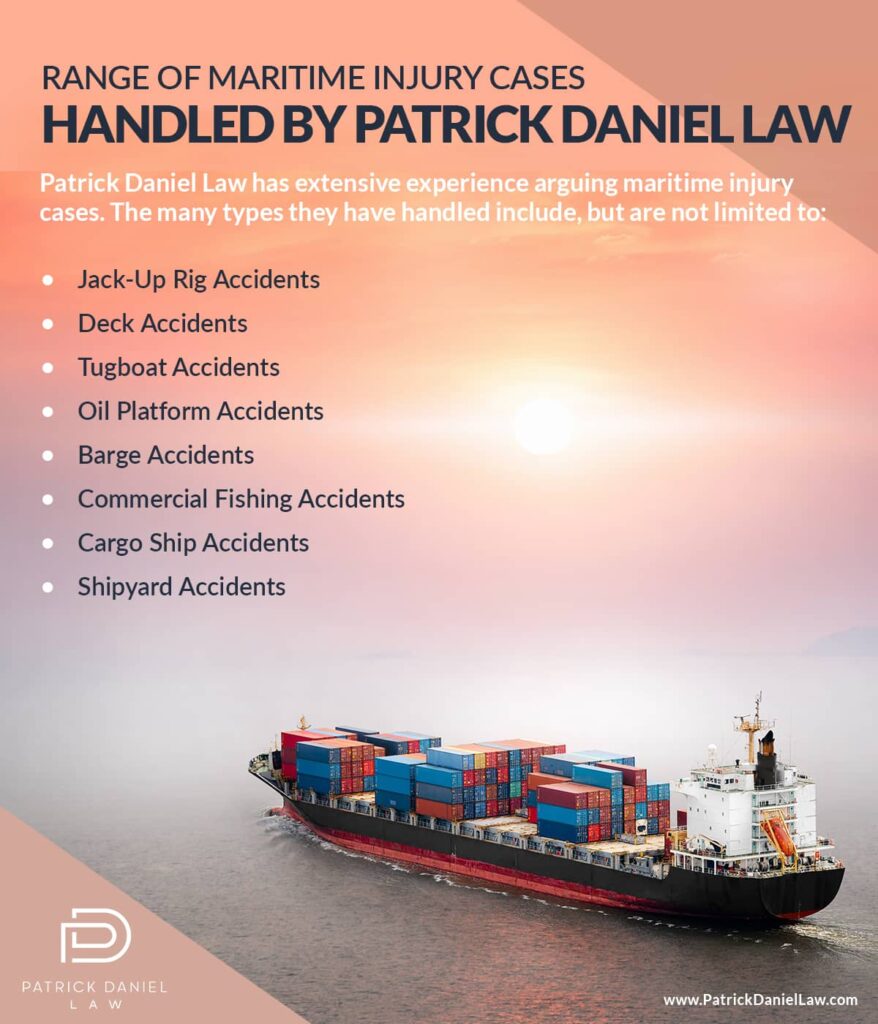

Here is a short list of the types of Houston maritime injury cases he has handled in both Texas and elsewhere:

If you sustained a maritime injury in Houston similar to the above, and would like a free consultation with our Houston maritime lawyers, or to find out more about our Houston maritime law services, please call (713) 999-6666 or contact us online.

Houston is much more than oil and aerospace. A recent study showed that Houston, TX is the No. 2 city in the country for jobs connected to maritime through the moving of cargo between U.S. ports. Only nearby New Orleans has more workers in the maritime industry. When you add up the workers from all Texas ports, it puts Texas as the No. 3 state in the U.S. in cargo transportation between American ports.

The Port of Houston includes over 200 private and public terminals, handling over 8200 seagoing vessels and 215,000 barges every year. Thousands of maritime employees call the Houston area home.

It should come as no surprise, then, that there are a multitude of maritime injury cases in Houston. Maritime workers who are injured at sea do not have many of the recourses that land-based workers do, and often have to hire a maritime injury lawyer in Houston to protect their rights and help them recover losses that stem from their maritime injury.

Maritime lawyers in Houston are plentiful, and they know admiralty law (maritime law) inside out, but experience is key. As an elite maritime injury lawyer, founder Patrick Daniel has litigated hundreds of maritime injury cases and has substantial recoveries for his clients.

But this process requires more than a successful courtroom attorney. Maritime work is grueling, unforgiving and raw, and any Houston, Texas lawyer who aspires to represent maritime workers had better know the work as well as he knows the law. That’s what sets Patrick Daniel Law ahead of other law firms in Houston, Texas. He knows the work. He grew in Louisiana and has 20 years’ experience in litigating maritime cases – some of it from the other side of the courtroom.

There are literally hundreds of maritime companies in Houston, and even though they claim to appreciate their employees and the sacrifices they make, you’re only one fall on a slippery deck or one tumbling pallet of cargo in heavy seas from discovering how much or how little they truly do care.

If you are injured at sea, don’t assume your employer will compensate you fairly and make sure your medical bills are covered. Any one of a host of Houston maritime lawyers will quickly point out that the ball game changes drastically when an injury occurs. Not only that, but the rules are different for maritime employees and land-based employees. Defendants in maritime law cases try to hide behind the nuances of maritime law, hoping the injured party is not up to speed on them.

For instance, Workman’s Comp does not apply to injuries suffered while at sea. But thanks to the federal Jones Act, maritime workers have the ability to sue their employers for compensation, and employers are held accountable to provide reasonably safe working conditions and to maintain their vessels so that they are safe and seaworthy.

So, what does maritime mean, anyway? Literally, maritime regards anything connected with the sea. This can be applied to commercial shipping and transporting or military activity. The set of laws governing maritime activity are known as admiralty law, a term used interchangeably with maritime law.

Maritime law does differ from the Law of the Sea, which governs international trade, mineral rights, jurisdiction over coastal waters, treaties and relations between countries. Admiralty cases are more local in concept, involving civil suits, individuals, companies and representatives of those companies.

The quick answer to the question of when you should call a lawyer after an accident at sea is “as soon as your ship docks in Houston.” If you have cell phone / Wi-Fi access and the privilege of making personal phone calls onboard, call or contact an attorney as soon as you can. If your ship allows workers to make personal calls, the management cannot take action against you if you use your time to call an attorney!

A common mistake some workers make is trying to appear to be a “team” player who doesn’t want to stir things up with the threat of a lawsuit. There could be quite a price to pay in order to protect an image that won’t even benefit you in the long run. A lot of Houston maritime workers – or former workers who can’t work anymore – wish they had called an attorney promptly after their accident.

Don’t try to determine by yourself if you have a case worth filing, despite all the blogs and websites that try to advise you on a DIY courtroom strategy. Make the smart move and call an attorney. Patrick Daniel has won so many admiralty cases that he can generally recognize a winnable case in just the first few minutes of a FREE consultation. If Patrick Daniel Law accepts your case, the legal fee will come out of the final settlement, and you will have no out-of-pocket expense.

Once you sail out of Houston and leave the national boundaries of the United States, even if you’re a U.S. citizen employed by a U.S. based company on a ship registered in the U.S., some laws designed for your protection no longer apply. Fortunately, other laws move into play that restore some of those protections, but in a different manner.

One such law is the Merchant Marine Act. It is an expansive law that includes regulations governing maritime commerce in U.S. waters between U.S. ports. Section 27 of the Merchant Marine Act, known as the Jones Act, requires that commerce between U.S. ports be transported only by American-built vessels. The Merchant Marine Act and the Jones Act are often used synonymously, but in actuality, the Jones Act is a part of the Merchant Marine Act.

The Jones Act also includes provisions that have seafaring workers’ rights at their core. Those provisions include (among many others):

The major provisions of the Jones Act apply to a special class of worker called a seaman. It is a legal recognition and very important to the process when injury claims are filed. But there is no binding definition of a seaman anywhere in the Jones Act or the Merchant Marine Act.

There is precedent, however, and maritime attorneys for both sides have to sort through past cases to determine if the plaintiff qualifies as a seaman. Simply being employed by one of Houston’s many shipping companies and spending time out at sea working that job is not enough to qualify as a seaman.

In lieu of a legal definition, most maritime lawyers and judges typically agree on the following definition, but the definition has undergone a metamorphosis of terminology over the years, and it is still subject to revision.

“Seamen means an individual (except scientific personnel, a sailing school instructor or sailing school student) engaged or employed in any capacity on board a vessel” (source).

That is nice and tidy, and a refinement of more cumbersome definitions that preceded it, but the Jones Act sets progess back a bit, insisting that to qualify as a seaman, a worker must spend at least 30 percent of his or her time onboard, out at sea. It’s a point upon which the opposing sides in an admiralty case can argue for hours. Without an over-arching definition to go by, however, it often becomes a stumbling block to the process.

Workers who don’t satisfy the terms for the definition of a seaman can still recover damages from the Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act (LWHCA). This federal law allows the injured party to recover losses for medical expenses, lost wages, rehab, etc. due to an injury, as well as survivor benefits if the injury causes the worker’s death.

This covers dock workers, ship builders and harbor construction workers who were injured in the wharf area of the harbor. The provisions of the LWHCA differ from standard Workman’s Comp laws and generally provide for slightly better compensation.

Without the safety net of Workman’s Comp, maritime employees often have to rely on the provisions of the Jones Act for compensation. In a few ways, maritime workers actually have a better system at their disposal, which is why contacting a maritime injury lawyer is of utmost importance when an injury has occurred.

With the provisions of the Jones Act to rely upon, maritime workers can file negligence lawsuits that go beyond the standard maintenance and cure for certain types of injuries. They can receive a more substantial settlement when they file a negligence suit and only have to prove that the employer’s negligence merely contributed to the injury in some way. In other words, the negligence doesn’t have to be the entire reason for the injury. It can actually play a very small role to be relevant.

Employers can contend that maritime workers must acknowledge the substantial inherent risks of working aboard a sea-going vessel, but that doesn’t absolve the employer or ship owner of liability when something goes wrong. Employers are expected to build and maintain the ship to code, make repairs as needed and provide a safe work environment. “Reasonable care” must be exercised, and they must foresee potential for mishaps and take steps to eliminate them.

Negligence is not limited to the way the ship is maintained. Sometimes, decisions that put workers at unreasonable risk must be held to accountability. Requiring workers to perform tasks in unsafe sea conditions, forego safety procedures, perform tasks for which they have not been trained or to stray from accepted practices regarding sea-going cargo are just a few examples of conduct that can be considered negligent.

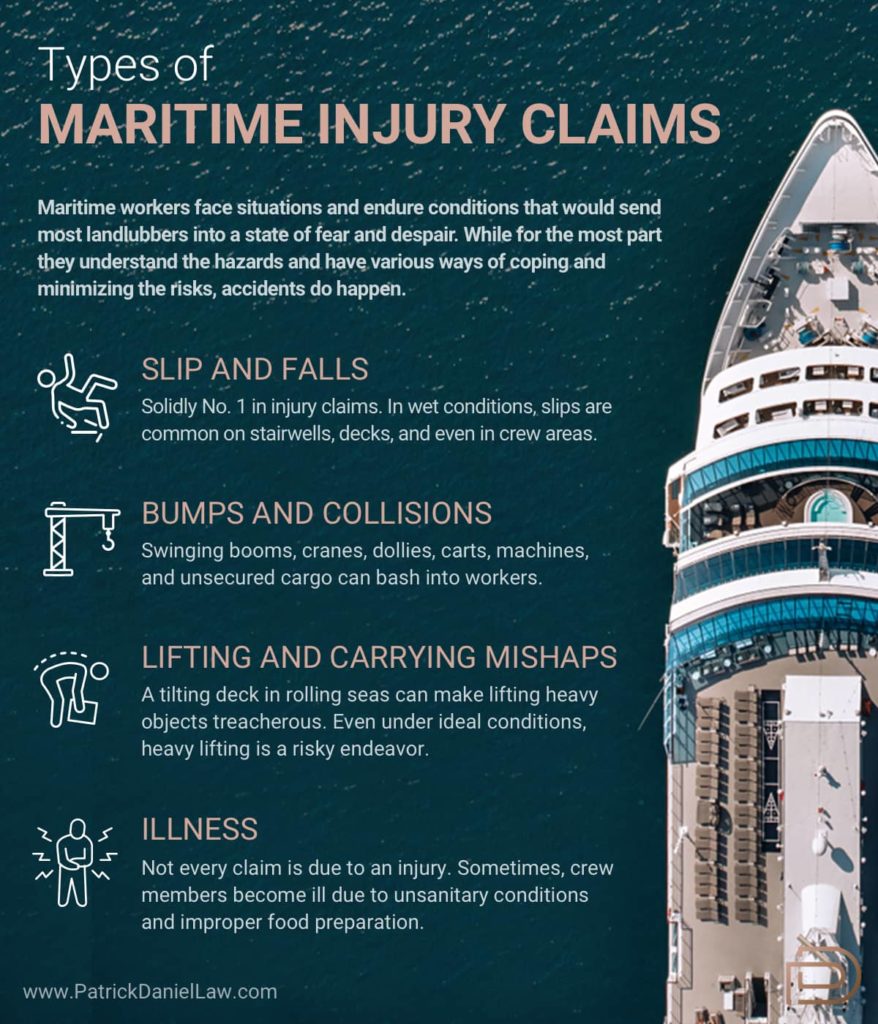

Maritime workers face situations and endure conditions that would send most landlubbers into a state of fear and despair. While for the most part they understand the hazards they’re exposed to and have various ways of coping with them and minimizing the risks, accidents do happen.

Among the most common injury-producing accidents suffered by maritime workers are:

When the ship is out to sea, an injured worker’s only medical option is the onboard medical staff, also known as the infirmary or sick bay. This can be a real asset or pose a real risk, if the personnel are inadequately trained. In extreme cases a transport helicopter might be needed, but weather and sea conditions can play a role in whether a helicopter can be dispatched.

An injury at sea is almost always breaking news around the ship. It’s impossible to keep something like that a secret. But regardless of the severity of the injury or the manner in which it occurred, it’s vital to maintain a grasp on the facts, because ultimately, it’s up to you to set the record straight on what happened.

As word of your injury reaches management, they will naturally want to talk to you. Be very, very careful of what you say, if anything. While you don’t want to be rude or uncooperative, you must protect your interests. And by all means, do not submit to a recorded statement. You cannot be compelled to provide a recorded statement at any point in the process.

Your compensation, if you decide to contact a maritime lawyer and file a claim, will be tied directly to the degree to which the employer or ship owner is negligent. Insurance company adjusters, and the attorneys on their side are masters of manipulation, and anything you say prior to the case going to court can be twisted and used against you. Don’t think you can outfox a seasoned pro!

Don’t sign any documents, approve any settlement offers or sign any statement without consulting a maritime attorney.

Do, however, fill out an accident report as part of the claims process. The difference here is when you fill out an accident report, you are in control. You have time to ponder your answers and clearly establish the facts without being put on the spot, trying to answer trick questions.

Get the names of any coworkers or witnesses who saw the accident or perhaps even noticed a hazard that might have contributed to your injury.

Contact Daniel Patrick Law in Houston immediately. They will go over your case and help you with the accident report and help establish a concise synopsis of the accident. Based on the confidential information you provide them, they can advise if your case is likely to be successful, and if so, advise how much compensation you might be entitled to.

The density of businesses in Houston – especially the businesses in the maritime industry – creates a community where information makes the rounds pretty quickly. When one of the companies is taken to court in a maritime injury suit, the other companies in the Houston area take notice.

Frankly, neither side in a maritime injury case wants the matter to go to court. Many don’t. In fact, most don’t. Often, when a maritime lawyer enters the case on the side of the victim, the opposing side suddenly decides it’s in their best interests to settle out of court.

The initial “sign here and we’ll be done with this” offer is often withdrawn and replaced with something more substantial and fair. Intimidation techniques generally subside, and for the most part, they’ll leave you alone and deal with your attorney directly.

Do not attempt to initiate a maritime injury claim yourself. Maritime law differs widely from the kind of laws you might be familiar with. It’s also in a constant state of flux. The Merchant Marine Act and Jones Act have been revised multiple times since their inception, and there are calls right now for new revisions, and even calls for their repeal.

A wide range of different jobs may constitute maritime employment. Many of these jobs meet the legal definition of a seaman under the Jones Act (and therefore entitles the worker to maintenance and cure and to bring claims for negligence in the event of an injury):

Maritime work also takes place at areas adjoining navigable waters, including harbors, piers, wharfs, shipyards, etc. However, if you are injured while working as a longshoreman, shipbuilder, or another job that does not meet the legal definition of a seaman, you will need to turn to the Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act.

A maritime injury is any type of harm that befalls someone working on or adjoining the navigable waters of the United States. Many different situations can lead to maritime injuries, including:

These and other accidents can happen on seafaring vessels, at ports, on oil rigs, and anywhere else that maritime work is performed. Maritime workers are entitled to compensation for injuries they sustain on the job, but the procedure for filing a claim is different from what those in landlocked professions need to do in the event of a workplace injury.

Few situations are more daunting than being hurt on a vessel at sea. You can’t simply call 911 and wait for the ambulance.

Seamen should do the following in the event of a maritime injury:

Many of the same steps apply if you are covered by the Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act – especially the importance of seeking prompt medical care and legal representation. One key difference is that longshore and harbor workers have 30 days instead of 7 to report an injury. Nevertheless, it is important to notify your employer as soon as possible.

Maritime law is complex. Also called admiralty law, it encompasses a range of federal regulations and state and local laws. Maritime lawyers need to have an in-depth knowledge of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (also known as the Jones Act), the Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act, and other legislation to represent clients effectively.

Without the assistance of a maritime lawyer, workers are likely to feel lost at sea when they file a claim for a job-related injury. A maritime attorney can:

The majority of maritime claims are tried in federal district court. Federal court proceedings are subject to different rules and procedures than cases handled at the county or state level. As such, it is of the utmost importance to work with an attorney who is well-versed in maritime law and has the experience to represent you in a court that many lawyers never see the inside of.

Maritime lawyer Patrick Daniel has been handling these cases on behalf of clients in Texas, Mississippi, and other areas of the Gulf Coast for 20 years. He is recognized for his dedication to and success in maritime law, consistently achieving results in high-stakes litigation.

Navigable waters are defined by federal law as “waters that are subject to the ebb and flow of the tide” and/or are used “to transport interstate or foreign commerce.” Although this definition obviously applies to offshore areas such as the Gulf of Mexico, it may also apply to rivers, lakes, and other bodies of water that are currently used, were used, or may be used for interstate commerce.

The location of the accident is key. If you are injured on the job on a waterway that does not meet the criteria for navigability, you may be limited to filing a workers’ compensation claim at the state level or taking legal action against a negligent third party (if applicable).

Under the Jones Act, seamen are automatically entitled to maintenance and cure in the event of a work-related injury. “Maintenance” refers to payments for day-to-day living expenses, while “cure” refers to the cost of medical care for injuries sustained in the accident. These benefits are paid until you reach maximum medical improvement (as determined by a physician).

Compensation for maintenance and cure is provided by the employer on a no-fault basis, meaning you don’t need to prove negligence in order to start receiving benefits. You do, however, need to prove that someone else is at fault in order to recover additional damages.

Jones Act claims are unique in that injured workers may be entitled to compensation for all losses stemming from a maritime accident if an employer’s negligence led to their injuries. If you can prove that wrongdoing on the part of your employer (such as failure to maintain the vessel, inadequate training for the crew, etc.) led to the accident, you may be entitled to compensation for the following losses:

The Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act (LHWCA) functions more like a standard workers’ comp program. Injured workers are generally barred from suing an employer, and benefits are limited to compensation for medical expenses, rehabilitation, and disability payments.

No two maritime injury claims are exactly alike. If you bring a lawsuit for negligence, it can take several months to more than a year for your case to settle. A resolution will take longer if the case goes to trial.

The doctrine of “seaworthiness” is a relatively low bar. Nearly any kind of dangerous condition can make a vessel unseaworthy for the purposes of a maritime injury claim.

Because workers often have ample grounds to bring a negligence lawsuit and recover substantial compensation if the claim is successful, maritime companies and their insurers are likely to mount an aggressive defense. They might argue that you are responsible for the accident or drastically undervalue the damages in your claim.

These and other tactics can lead to what seem like interminable delays for workers recovering from serious and catastrophic injuries. However, it is important to be patient. A favorable outcome can make the difference between having the compensation you need to get on with your life and being unprepared to face the burdens of your injury in the future.

Workers in the offshore oil industry likely have two options for legal recourse if they are injured on the job. The location of the accident and the nature of your job will both play a part in which type of claim you should file.

If you work on a jackup rig, platform supply ship, or another vessel that moves along the offshore navigable waters, you likely qualify as a Jones Act seaman. As a seaman, you can bring a claim for maintenance and cure, as well as pursue additional compensation if the vessel on which you were working at the time of the accident was not seaworthy.

If you work on a deepwater drilling platform or another permanent offshore structure, however, you would probably not meet the “in navigation” requirement to bring a claim under the Jones Act in the event of an accident. The Longshore and Harbor Workers’ Compensation Act will likely apply in this situation instead.

Despite the thousands of maritime injury cases involving Houston-based maritime firms and their employees, there’s always something new that comes along. The following cases from around the U.S. set precedents for similar cases that may follow.

American Seafoods, owner of the ship, American Dynasty, was found negligent for not providing a safe work environment for a crane operator who fell trying to reach a control that should have been more accessible.

The worker was required by his supervisors to operate a mid-ship crane on the trawl deck. Normally, the crane could be operated by a wireless remote control, which allows workers to use the crane during inclement weather. However, on the day of the accident, the remote control was not available, having been taken out of service by the chief engineer so that the crew wouldn’t misplace it.

In order to use the crane, the worker had to climb a ladder to reach the control tower. The ladder was sub-standard, even by written company policy that asserted that the ladder must have evenly-spaced rungs. This ladder did not have evenly-spaced rungs or a hand rail, and the worker fell, suffering a serious knee injury.

The case was won on the basis of the ladder that didn’t meet even the company’s written safety policy. The judgment was for $900,000.

This case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and established a modern precedent for what constitutes seaworthiness and reasonable care.

Frank C. Mitchell slipped on a stairway aboard the fishing trawler Racer when he encountered slime on the handrail. He sued on the basis of negligence and of the ship’s unseaworthiness. The ship’s owner said the condition of the handrail was unknown to its crew, was temporary and that reasonable care had been applied in the maintenance of the vessel.

A jury sided with both parties, allowing Mitchell to collect on standard maintenance and cure for negligence, as provided by the Jones Act, but ruling for the defendant on the charge of unseaworthiness.

Mitchell appealed the ruling, charging that the presiding judge was in error when he instructed the jury that in order to rule for the plaintiff’s petition for unseaworthiness, the defendant had to have known about the slime on the handrail and chose not to address it. The appellate court sided with the lower court, based on the presumption that the plaintiff had failed to prove the ship’s crew knew about the slime beforehand. But when the case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court, the case was overturned.

In writing the opinion of the court, Associate Justice Potter Stewart said that a ship owner’s responsibility to provide a seaworthy vessel goes beyond simply applying reasonable care, and that a temporary condition that renders a vessel unseaworthy does not relieve the owner from liability.

Gautreaux (first name not available) was severely injured when a manual crank handle that he had laid on top of an electric winch flew off the winch when the winch suddenly activated. He had been using the manual crank to free the winch, which had become stuck. The crank handle struck Gautreaux in the eye and face.

Gautreaux sued Scurlock Marine for negligence and failure to provide a seaworthy vessel, saying he had not been properly trained in the use of the manual crank. Scurlock countered, saying Gautreaux had been thoroughly trained on the towboat Brooke Lynn, where the accident occurred, and had been trained specifically on the use of the manual winch crank. They said he should have exercised better care for his own safety.

According to the Jones Act, a seaman need exercise only “slight care” for his own safety, while his employer is held to a much higher standard to assure a safe work environment. Scurlock’s attorneys argued that the court had blindly followed an incorrect statement of the law.

The court said that regardless of the correctness or fairness of the “slight care” provision of the Jones Act, it could not alter it, adding that it would be up to higher courts to change the interpretation of the law and to lawmakers to change the law itself. The jury apportioned 95% of the fault to Scurlock and 5% to Gautreaux, and awarded him $854,000. That figure was later reduced by an appellate judge to $736,925.

If the case examples above leave you scratching your head, you’re not alone. Maritime law is complicated, subject to various interpretations and subject to revisions.

Your best choice for resolving your maritime injury case is Patrick Daniel Law. Patrick Daniel started out working maritime injury cases from the defense side. He cut his teeth learning the tricks of maritime negligence defense – concealing evidence and witnesses, delaying tactics, stalemating and intimidation.

Twenty years ago, he switched over to the plaintiff’s side of maritime law and has become a passionate advocate for those suffering from maritime injuries.

He’s not only a master craftsman in the courtroom and the negotiating table, as an expert trial attorney, but he also knows the work. He’s a Louisiana native and grew up around the people of the maritime industry. He’s even represented people working on the outer continental shelf and high seas, including offshore oil rigs, jack-up rigs, drilling rigs, anchor handling vessels, towboats, crew boats and more.

You won’t be able to perplex Patrick with maritime vernacular, and neither will those on the other side of the courtroom. Patrick Daniel Law’s practice is not limited to Houston, Texas, or even the Gulf Coast. He has had clients from Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida and as far away as North Carolina.

Contact Patrick Daniel Law for a FREE consultation. If you have a winnable maritime case, we’ll tell you. If you don’t, we’ll tell you that as well. We charge no fee until your maritime injury case has been won on your behalf. Don’t let an unscrupulous company or ship owner avoid their obligation to pay you for your loss. The law is on your side and so is Patrick Daniel Law.

Top Truck Accident Lawyer in Pasadena

Top Truck Accident Lawyer in Pasadena Best of The Best Attorneys

Best of The Best Attorneys Best of the Best Houston Chronicle 2021

Best of the Best Houston Chronicle 2021 Best Motorcycle Accident Lawyers in Houston 2021

Best Motorcycle Accident Lawyers in Houston 2021 American Association for Justice Member

American Association for Justice Member The National Trial Lawyers 2016 – (Top 40 under 40)

The National Trial Lawyers 2016 – (Top 40 under 40) Multi-Million Dollar Advocates Forum 2016 (Top Trial Lawyer)

Multi-Million Dollar Advocates Forum 2016 (Top Trial Lawyer) Million Dollar Advocates Forum 2019 (Top Trial Lawyer)

Million Dollar Advocates Forum 2019 (Top Trial Lawyer) America’s Top 100 Attorneys 2020 (High Stake Litigators)

America’s Top 100 Attorneys 2020 (High Stake Litigators) Lawyers of Distinction 2019, 2020 (Recognizing Excellence in Personal Injury)

Lawyers of Distinction 2019, 2020 (Recognizing Excellence in Personal Injury) American Institute of Personal Injury Attorneys 2020 (Top 10 Best Attorneys – Client Satisfaction)

American Institute of Personal Injury Attorneys 2020 (Top 10 Best Attorneys – Client Satisfaction) American Institute of Legal Advocates 2020 (Membership)

American Institute of Legal Advocates 2020 (Membership) Association of American Trial Lawyers 2018 - Top 100 Award recognizing excellence in personal injury law

Association of American Trial Lawyers 2018 - Top 100 Award recognizing excellence in personal injury law American Institute of Legal Professionals 2020 (Lawyer of the Year)

American Institute of Legal Professionals 2020 (Lawyer of the Year) Lead Counsel Verified Personal Injury 2020

Lead Counsel Verified Personal Injury 2020 The Houston Business Journal 2021

The Houston Business Journal 2021